9.1. I/O framework¶

JULES version 3.1 saw a complete rewrite of the I/O code to use a more modular and flexible structure. This section attempts to give a brief description of the low-level I/O framework, and explains how to make some commonly required changes. This section requires a good knowledge of Fortran.

9.1.1. Overview¶

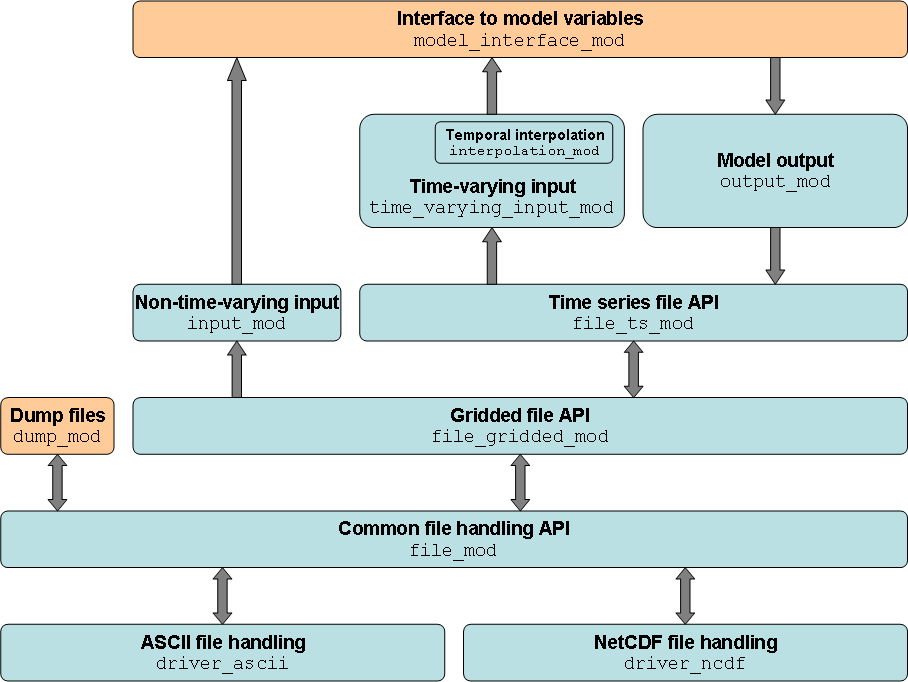

The JULES I/O code is comprised of several ‘layers’ with clearly defined responsibilities that communicate with each other, as shown in the figure Modular structure of the JULES I/O code (the relevant Fortran modules for each layer are also given). The blocks in orange are the JULES specific pieces of code - in theory, the rest of the code could be used with other models if different implementations of these modules were provided.

Modular structure of the JULES I/O code

The core component in the I/O framework is the common file handling API. This layer provides a common interface for different file formats that is then used by the rest of the code. The drivers for ASCII and NetCDF files implement this interface. The interface is based around the concepts of dimensions and variables, much like NetCDF (except that nothing is inferred from metadata - all information about variables and dimensions must be prescribed), but adds the concept of a “record” to that:

- Dimension

A file has one or more dimensions. Each regular dimension has a name and a size.

One dimension is special, and is referred to as the record dimension. It has a name but has no defined size. A typical use of the record dimension is to represent time.

- Variable

- A file has one or more variables. The size of each variable is defined using the dimensions previously defined in the file. Each variable can opt to use the record dimension or not - if a variable uses the record dimension it must be the last dimension that the variable has.

- Record

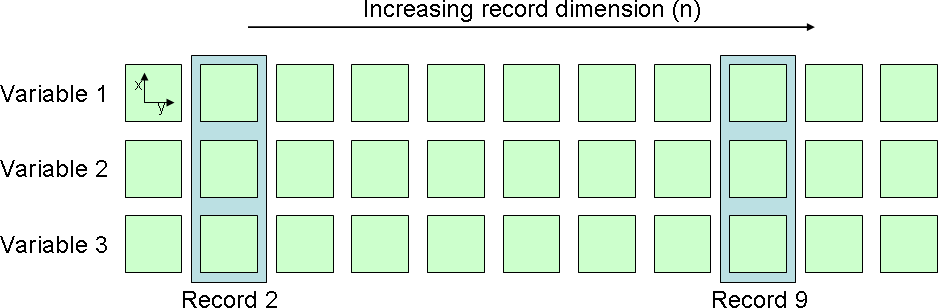

A record is the collection of all variables at a certain value of the record dimension. The figure Records in a file gives an example of this:

Records in a file

In the figure, each variable has dimensions x, y and n, where n is the record dimension. Each green box represents the (2D plane of) values of a variable for a certain value of n. A record is then the collection of all variables at a certain value of n.

A good analogy is the lines in an ASCII file, where each column represents a variable and each line is a record (in fact, this is a generalisation to multiple dimensions of that exact concept).

Files keep track of the record they are currently pointing at (it is the responsibility of the file-type drivers to do this in the way that best suits the file format they implement). When a file receives a read or write request for a particular variable, the values are read from or written to the current record.

The record abstraction also allows two useful operations - seek and advance. When a file receives an instruction to seek to a particular record, it sets its internal pointer so that read/write requests access the given record (a use of this within JULES is looping the input files round spin-up cycles). An advance instruction just moves the internal pointer on to the next record.

The routines in file_mod define the interface that each file-type driver must implement, and are responsible for deciding which driver to defer to. Support for a file format is provided by implementing this interface and declaring the implementation in file_mod. This is discussed in further detail in Implementing a new file format.

The gridded file API then imposes the concept of reading and writing 3D cubes (x and y dimensions and an optional z dimension) of data on top of the common file handling API. The underlying files may have a 1D or 2D grid (see Input files for JULES), and this layer handles the grid dimensions transparently. It is this layer that handles the extraction of a subgrid from a larger grid (see file_gridded_read_var and file_gridded_write_var).

The time series file API builds on the gridded file API by explicitly presenting the record dimension as a time dimension. It provides an interface that allows users to treat multiple files (e.g. monthly files, yearly files) as if they were a single file (i.e. seek and advance will automatically open and close files if required).

The input and output layers interact with the model via an interface provided by model_interface_mod. model_interface_mod allows the input and output layers to read values from and write values to the internal model variables. This is discussed in more detail in Implementing new variables for input and output. The input and output layers use the time series file API to read from and write to file.

This should provide a reasonable introduction to the JULES I/O framework, but looking at the code is the best way to learn about it.

9.1.2. Implementing new variables for input and output¶

The only I/O code that needs to be modified to add new variables for input and output is in model_interface_mod (the routines in src/io/model_interface). All interaction between the I/O code and the model happens in this module (apart from reading and writing dump files).

Before adding any code to model_interface_mod, the variable the user wishes to make available for input and/or output must be accessible to model_interface_mod. This is usually accomplished by placing the variable in a module and importing the module into model_interface_mod where required, e.g.:

! Declare the variable in a module

MODULE my_module

REAL, ALLOCATABLE :: my_var(:)

! ...

END MODULE my_module

! ... Later, in model_interface_mod

USE my_module, ONLY : my_var

model_interface_mod contains several routines, each of which is responsible for providing a specific piece of information about model variables to the input and output layers. Each of these routines uses a SELECT statement to choose which variable to operate on - implementing a new variable for input or output is as simple as adding a new CASE to the appropriate SELECT statements.

- model_interface_mod, get_var_id, get_string_identifier

Note

Required for both input and output variables.

Externally, variables are identified by the string identifiers seen in this document (e.g. driving variables). Internally, each variable is assigned a unique integer id - these are defined as PARAMETERs in model_interface_mod.

get_var_id takes a string identifier and returns the associated integer id, and get_string_identifier does the reverse.

- get_var_levs_dim

Note

Required for both input and output variables.

Takes an integer id and returns the name and size of the levels (z) dimension for that variable (remember that all input and output uses 3D cubes with x and y dimensions and an optional z dimension). If no z dimension is required, the empty string should be returned as the dimension name and 1 as the dimension size - internally, variables with no z dimension are treated as if they have a z dimension of size 1, but that dimension does not exist in the file(s).

- get_capture_point

Note

Required for output variables only.

Takes an integer id and returns a value indicating whether output values for the variable should be captured at the start or end of a timestep (see JULES output).

In order to remain consistent with the current output, state variables should be captured at the start of a timestep and fluxes/rates should be captured at the end.

- get_var_attrs

Note

Required for output variables only.

Takes an integer id and returns the attributes that will be attached to the variable in output files.

- populate_var

Note

Required for input variables only.

Takes an integer id and a (x,y,z) cube of data on the full model grid, and populates the associated model variable using that data.

- extract_var

Note

Required for output variables only.

Takes an integer id, extracts the values from the associated model variable, and returns those values as a (x,y,z) cube of data on the full model grid.

map_from_land and map_to_land are provided as utilities for use with variables that are defined on land points only. tiles_to_gbm is used to provide gridbox mean diagnostics for model variables that have one value per surface tile.

As always, the best way to go about implementing new variables for input and output is to follow the examples that are already there.

9.1.3. Implementing a new file format¶

To understand how to implement a new file format, it first helps to understand how the common file handling layer works under the hood.

Each of the routines in file_mod (see files in src/io/file_handling/core) takes a file_handle as its first argument. The file_handle is a Fortran derived type that contains a flag indicating the format of the file it represents, and each of the routines in file_mod contains a SELECT statement that defers to the correct implementation of the routine based on that flag.

file_handles are created in file_open. Each file format implementation defines a list of recognised file extensions, and the appropriate file opening routine is deferred to by comparing the extension of the given file name to the recognised extensions for each file format.

To implement a new file format, an implementation of each of the routines in file_mod must first be provided (the implementations for ASCII and NetCDF formats should be used as a reference). A new CASE deferring to the new implementation should then be added to the SELECT statement in each of the routines in file_mod. The recognised file extensions for the new format should also be added to the checks in file_open to allow the new the file opening routine to be called.

Implementations of these routines for ASCII and NetCDF file formats are given in driver_ascii (see src/io/file_handling/core/drivers/ascii)and driver_ncdf (see src/io/file_handling/core/drivers/ncdf) respectively. These should be used as examples of how to implement a file format.

These two file formats suffer from opposite problems when implementing the concepts of dimensions, variables and records. For NetCDF, the concepts of dimensions and variables already exist, but the idea of a record has to be imposed. For ASCII, the concept of a record is a natural fit (think lines in a file), but the concepts of dimensions and variables have to be imposed. Between them, these implementations should provide sufficient examples of how to implement a new file format.